A New Plane

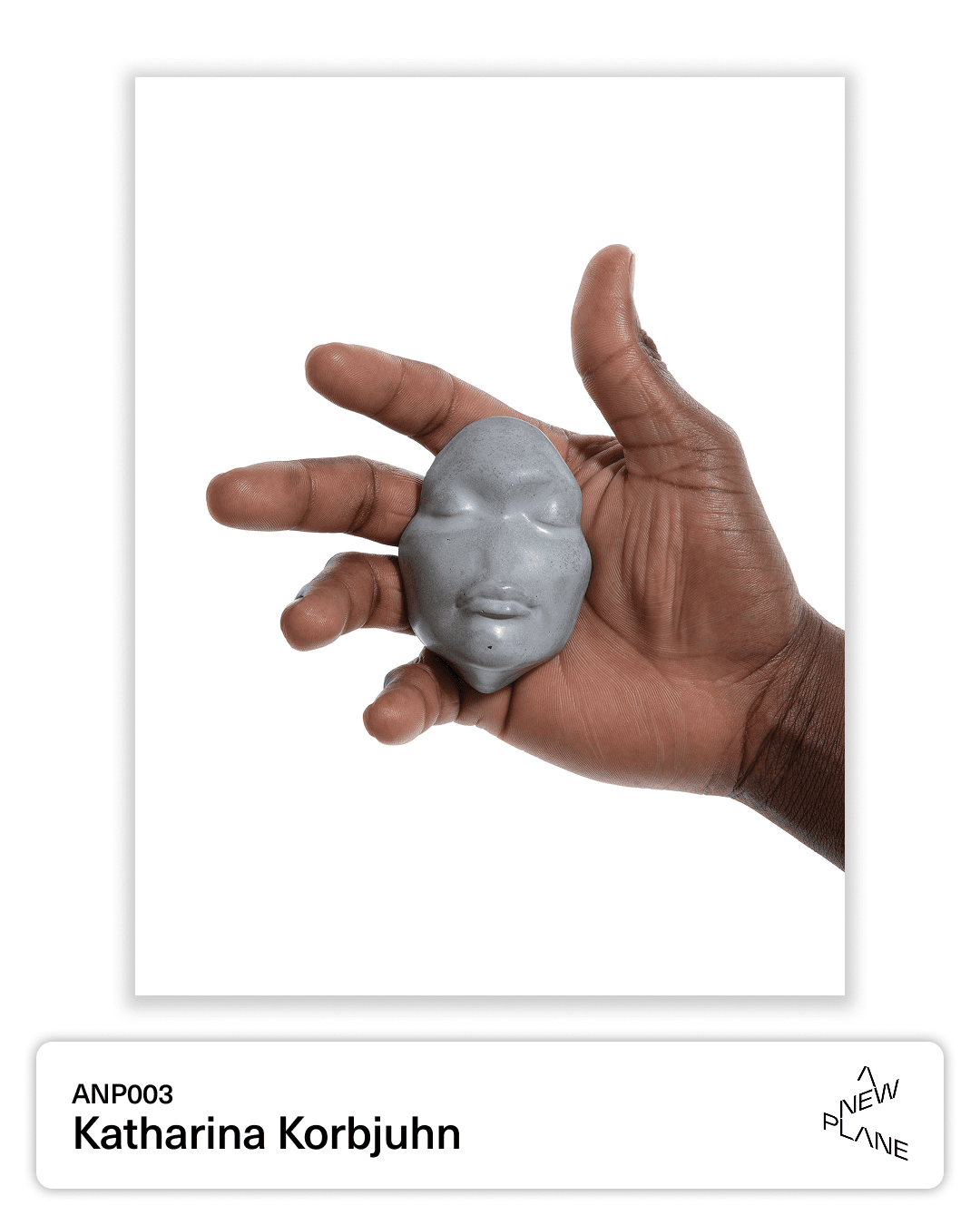

ANP003: Katharina Korbjuhn

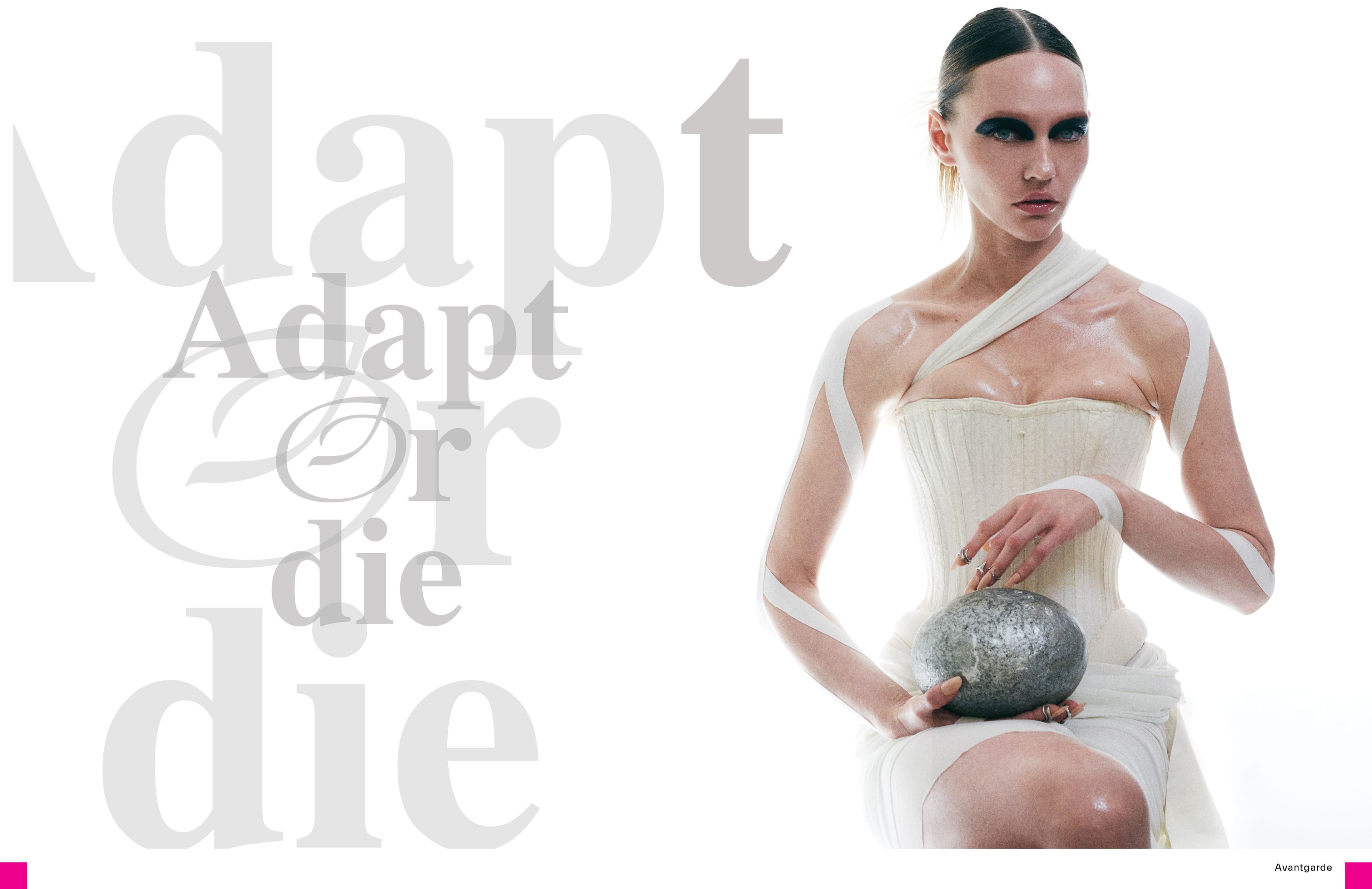

By her own admission, Katharina Korbjuhn is much more driven by thought than she is by aesthetic. An outlier in the world of fashion, the creative director and editor’s projects vary wildly in scope and execution, but are connected by a commitment to making space for important ideas. Whether revitalising legacy brands like Chloé, Mugler, Schiparelli and Tod’s Group or bringing the insider bible System Magazine online, or in her new appointment as CBO of Lady Gaga’s Haus Labs, her work is unmistakable for its irresistible synthesis of cultural commentary, media theory and razor sharp aesthetic sense. This is perhaps best represented by the pioneering Paradigm Trilogy, which reinvents the fashion publication by aligning three themes with three different cities and three different objects.

The first, Avantgarde & Kitsch, was released with boxes of matches in New York and charted a topology of cultural production across increasingly byzantine platforms and media ecosystems. Man Vs. Machine dropped in Berlin, accompanied by a stone mask sculpted by artist Hamzat Raheem in the likeness of model Paloma Elsesser’s face, and explored how technology, in particular AI, might influence the future of creativity. The third and final edition, Recognition Vs. Expression, took the form of a film, written and directed by Korbjuhn, that was unveiled in Paris alongside a bottle of perfume called ‘Sweat’, which captures the scent of the human body.

Rather than simply adding filmmaking to her seemingly inexhaustible set of skills, Paradigm Trilogy’s swerve to the cinematic reflects Korbjuhn’s own feelings about the failure of contemporary criticism to address the complexity of the cultural spheres through which we move. Feeling jaded by the limitations of the written word and mired in notions of intelligence, human or artificial, with Recognition Vs. Expression, Korbjuhn turns back to the body, offering embodiment as the only way to consolidate understanding in an era of overstimulation and information overload. Providing us with a glimpse of her singular ability to navigate culture, Katharina Korbjuhn explains why it’s vital to take responsibility for the creative act, why we shouldn’t be scared of AI and how the films of Michael Haneke reveal emotional truths about a world mediated by technology.

Why was it that you chose to make the final issue of Paradigm Trilogy a film?

KK

I knew people would love the second issue because it’s exactly what people want to talk about. Artificial Intelligence, Tech-Angst, the Future Unknown. It was critical theory on fleek, feeding into the intelligentsia crowd. But I felt like I was adding to the problem. The solution to capitalism and the problems it creates will not come from cultural writing. I’m perpetuating the system by doing so. It left me feeling quite nihilistic. I decided for Paradigm III: Recognition Vs. Expression to be a film as it is the most embodied medium. It allows for complex concepts to be presented in a way that is accessible to all. I wanted to ask questions that felt simple or banal but would lead the reader closer to connecting back to themselves. In Thailand, a psychic once asked me: Who are you now? That question completely derailed me. When we let go of programmed knowledge of what we think we should say, the answer comes. But it’s felt, not thought.

There are elements of embodiment in creative direction. You can just have a feeling about something. How do you apply the ideas from Recognition Vs. Expression in your practice as a creative director?

KK

We must understand that our creation has meaning, and our responsibility as artists is to inject meaning whenever possible. We should be able to sign up to the world that our creation represents, especially against the backdrop of Balenciaga, the Yeezy aesthetic, and artists like Anne Imhof. I have nothing against them. It’s the use of fascist and brutalist tropes of power to sell goods in market capitalism that’s disturbing because you’re using an aesthetic without distancing yourself from its native meaning. For artists, I believe mental hygiene is the biggest part of our work. If we are in touch with ourselves, what we create will come from the right place. It’s about staying in that liminal space where up and down connect. It’s not actually about putting pen to paper. It’s everything before and around that. Paradigm III was dedicated to this space.

Why do you think that film feels like the most effective technology for embodiment at the moment?

KK

Film is capitalism’s poster child, the perfect Trojan Horse. It can reveal absurdities and show us other worlds while being seen as a stabilizing force in the system. It is a respected art form, it has huge reach and, at a time when we’re looking at the end of stories, the end of the future, it is predicated on storytelling, which is the glue of humanity. Maybe Michael Haneke’s Funny Games is the thing to mention here: a splatter film that mocked American splatter films. It became a cult film to some and a middle-finger-move to others. This kind of double-entendre subtly flies in film. Can you believe it? Nuance!

How would you place the fashion film in the context of the history of image making?

KK

I think fashion should be part of film. Give me a documentary, or give me fab costume design in a movie. A fashion film is a mood. I don’t know if we need a mood. At its best, a fashion film is a movie, or a music video.

One of A New Plane's earliest projects was a music video for Björk, who is the subject of a section of Recognition Vs. Expression. In the clip, Björk is talking about how you introduce soul into electronic music, a question you then pose to the viewer: “what's the last thing that you put soul into?” How might one put soul into CGI?

KK

By adding perspective to the tool. As a tool without soul, CGI can simplify processes and make things cheaper. A good example is e-commerce photography. But when used purposefully, it can serve as a great tool for looking at the self and our physical body in relation to technology. I watched your Leon Dame CGI video and I was thinking: Why is this interesting? It’s energetic. There’s a beat and a body in motion, but what I truly see is an individual trying to look at itself from the outside. It’s almost like looking at ourselves as a specimen, studying ourselves and the extension of our borders, the borders of self. To understand how to use technology in fashion, we need to understand the role of the body.

I think there’s an intrigue in CGI aesthetics in the same way that there was an interest in psychedelics in the '70s, as a way of dissolving and reassembling reality. Quantum physics suggests that physical matter is constantly in motion and not, in fact, ‘solid’. Dalí’s melting clocks might be a more realistic depiction of reality than the way we see it. With CGI, we’re given a tool that can stretch our visual world into something that is maybe more accurate to how it feels to us, rather than how it looks to us.

We see 3D scanning and motion capture as in some ways analogous to enfleurage, or the practice of extracting scent, which you explore with the perfume released alongside Recognition vs Expression. In the film you position it as the extraction of an essence of a person, the "hot girl" sweat of a body, which you use to synthesise a "smell to exit simulation." Is there a similarity between that process and motion capture as a way of extracting a digital essence of a body?

KK

By extracting someone’s scent you’re 4D scanning, basically. Scent is a memory, of course, but it is also a transmitter of information, of things that we don’t know and don’t remember. The idea of the scent came about when the metaverse was being announced. At the same time, this Black Mirror episode was released where they were all in these bunkers putting on VR goggles to have a nice time after work and Harry Styles was in that film Don't Worry Darling, where they don’t know they are in a simulation. I thought to myself: How will we know what’s real and, frankly, does it matter? I know when I smell my boyfriend’s armpit that I am definitely not dreaming. In that way, enfleurage is a reminder, both a memento mori and a reminder of the now. But what is motion capture?

When we're creating a person's digital avatar, we've done a few now, the process of motion capture is always the moment when you truly feel somebody's digital likeness.

KK

For me, the difference is that Enfleurage is a tool for capture that necessitates the analog anchor, whereas 3D scanning is a tool that does not need the original anymore. Why do we need ABBA if we can have something that looks like it and sounds like it? ABBA Voyage is then ABBA. It’s Walter Benjamin: Can the spirit of the artwork be recreated? The question is, how much is spirit part of our experience of something? lf I see them like that, and they’re sounding like that, how important is it that I know it’s not them?

If the aura of a performance is something you might be able to preserve in the 3D scanning and motion capture process, which is a synthesis of physical gesture and technology, do you perceive an absence of spirit there? Or can spirit be simulated?

KK

That’s maybe the most important point - is there an absence of spirit? There definitely isn’t ABBA’s spirit in there, but is the spirit of the person that created the simulation in there? Sherry Turkle argues that our digital expression is as spirited as our real expression. It’s not the computer and us. It’s just us. Technology is being vilified and used by corporate interests in order to justify negative human behaviour. We shouldn’t be afraid of AI, unless someone decides they want to use it to replace humans. But that decision will still come from a human! The way it’s being talked about is giving it so much power, when it’s simply a tool. It’s as much a wheel as it is a part of a car. Everyone wants everything to be AI and CGI now.

Are those requests you’re getting from clients? What are the reasons for them wanting to use it?

KK

They think it’s the future. Someone told them it’s the future, so they think they’d better get on it now. It’s like when Instagram Threads came out, and everyone thought it was the future, so they better have an account. Have you ever been on Threads? All these brands are just talking to themselves.

Is there a broader point to make about AI here? If you have all these brands coming to you demanding the use of AI, but they’re all just talking to each other on social media, will brands start using AI agents to interact with each other and cut out the audience entirely? Clients want to use AI, then their AI agents talk to the AI agents of other clients.

KK

Oh, 100%. I think this is already happening. I don’t need to open Instagram to know what’s going on. The algorithm dictates who sees what; we’re not in charge of that. Marketing is in a dysfunctional mode. I need to convince brands that ask for a shoe rendered in CGI to add a human element. Usually, the low number of likes they will get is an effective way to scare them out of it. But the argument for likes has decreased, brands have understood that it’s not about achieving a majority, but really harnessing focus groups. It comes back to taste. Using chatGPT has made me realize how the importance of taste will just skyrocket. At the outset of fashion photography taste was very important, but when fashion became an industry, around the ‘80s and ‘90s, it was pushed aside by aesthetic trends. Now, with the appearance of new technology, we’re going back, taste will give you work. I'm quite thrilled about it! I've still got something to sell.

How do you defend your taste as a creative director?

KK

My work is quite elusive. I don’t have a dominant aesthetic. For me, thought produces aesthetic demand. A strong idea justifies the tools, it tells you what it needs. It’s gotten easier for me to defend my work in this new technological cycle, where you can infinitely reproduce an aesthetic if you have the right keywords. Ideas are not such easy prey.

Film is a technology that you've used successfully to inscribe a certain sense of physicality in performance and direction. Can we think of CGI/AI as a technology to get closer to the body?

KK

CGI and AI are useful tools to get closer to an understanding of the physical in a digital world. In fashion, they are at their best when they play with the codes of our genre, not when fashion is trying to abide by their codes. That’s when we can comment on our sense of self through technology. I’m really interested in Michael Haneke at the moment because I think he captured the early appearance of technology and its influence on human life as mainly being a tool of surveillance. In Benny's Video, for example, the young boy starts taping everything, which gets at this idea of how our life becomes mediated by technology.

What is your personal relationship with these technologies at the moment?

KK

I always think about how we grew up in a system where we learned knowledge. Now, it’s less about being a container for knowledge, because we can access all of it at all times. It’s more about understanding the prompts. If you know how to put in the right prompts, you’re moving at light speed in this world. I recently had a conversation with a physicist about the hard problem of conscience, which argues that the idea of our world as split into material and non-material is an incorrect assumption and that even consciousness has a material expression. Every thought we have requires physical transmitters and molecules to move. That makes a whole lot of sense to me, it dissolves the border between digital and our analog worlds. So, when you’re asking me about my relationship with technology, you’re asking me about my relationship with myself.

Have these ideas influenced your approach to what you do?

KK

For the most part in fashion, technology, and as a substitute the idea of a future, is applied as an aesthetic. It’s more an idea of the future that is expressed visually, rather than an actual future. I wrote about our relationship to technology in issue two of Paradigm Trilogy, ‘Man Vs. Machine’, in which I said the future will look exactly like right now. Maybe there are fewer cables, but it will not look like The Matrix. I’m always curious why we're coming up with this hyperbolic aesthetic. I think we live in a time where, more than ever, the future doesn’t seem like an achievable thing. If we look at what fashion is constantly doing, we’re seeking the future in our past. We have the weirdos, like A New Plane, that are still pushing in that direction, but for the most part, people have given up on thinking about a far future that will most probably not be lived.

Before we had access to the internet, you could go down a rabbit hole and at some point you might try to recreate and riff off the work that you came across. Now, because we have so many different directions to go in, there's always something new to happen upon, so we never quite fall down the rabbit hole.

KK

That is very real. I recently watched September 5th, which is about the Munich Olympics in 1972, the first time a terrorist attack was live streamed. 900 million people were watching on ABC News, it was bigger than the moon landing. This was a decisive moment that changed history. Information was immediately transferred to the viewer without curation or editing. That made me think about how the delay in information in a less mediated world was good for us. The world seemed smaller. Now, we’re exposed to a cacophony of information that creates less knowledge and understanding. It almost feels like we’re in a blackout. We can know everything at any second, so why bother?

Is that key to understanding how cultural production has changed since you published the first volume of Paradigm Trilogy back in 2020?

KK

Regarding cultural production, I think AI has taught us that content should cater to our expectations and that things should be easy and entertaining. That’s really bad. Art shouldn’t be a service industry. I cite the 2016 DIS Biennial in Berlin, ‘The Present in Drag,’ as the end of culture. ‘Post-Internet Art,’ a prominent category at the time that has since vanished, was seeking answers about the uncomfortable: a post-capitalist future led by technology. Instead, we’re back to landscapes and figurative painting, which not even the artists or gallerists are excited about. Status quo reloaded.

Subscribe to our Substack to get interviews and memos from A New Plane delivered straight to your inbox every month.

⁕

1 / 17

Interview

About